8,000 miles for milk

Mixing milk with a socially minded marketing agency and farmers in East Africa can make for impressive health benefits all around.

Mitch Apley is VP, director of broadcast/print production, AbelsonTaylor. Tristen George is VP, director of experience design. Kristen McGirk is VP, account director. Stephen Neale is senior VP, executive creative director. Dale Taylor is president and CEO. Joel Witmer is senior editor/cinematographer.

DALE: Well, it actually began – I’m not even sure when. Maybe 10 years ago, maybe even longer ago than that.

JOEL: AbelsonTaylor had been a longtime supporter of Heifer International. Every year since I’ve been here we’ve done a holiday card – a website where we let clients know that we’ve made a donation in their name to Heifer International.

KRISTEN: We’ve sponsored camel projects in Africa and bees in South America and goats in the Middle East, a whole variety of projects around the world. And then about two years ago, Heifer came to us and said, “We’d like your help to build out this East Africa Dairy Development project.”

STEPHEN: One of the things that we’ve always liked about Heifer is that they are very much about sustainable systems. They donate animals to families who then can use those animals to build their own family-sustaining system. It’s not just about giving money but actually creating self-sustaining systems through which these families around the globe can flourish. So when we found out about East Africa Dairy, we wanted to see if there was anything that we as a health and wellness agency could do to help increase the uptake or address any other issues. And just as with our regular work, the only way we could find out about the challenges the East Africa Dairy program was facing was to immerse ourselves into it.

MITCH: We’d never had any imagery from Heifer’s work in Africa, we’d never had any videos, certainly. So I said to Dale one day, “Hey, have you ever actually gone over to Africa to see your donations at work? It would be nice if we actually had some footage.” He said, “Well, I don’t know if it’s worth it just for that.” So I actually started talking about it with Kristen a couple of years ago, about the idea of, in addition to whatever financial support we give to Heifer, maybe we can create a promotional video for them, and that would help drive further donations. If we can create a motivating video – and they have video communications, but honestly, they’re a humanitarian organization, not a marketing company.

TRISTEN: We needed education on the culture and we needed education on how the community was interacting with the milk industry, with their own cows, what they were doing with their milk. We needed to kind of get on the ground to do real field research.

STEPHEN: So Heifer set up a trip where we could take a look around, troubleshoot, see how the program was working successfully in one area, and maybe take what we learned from there and see if we as an ad agency could help quicken the uptake in other areas. We went over there with two purposes in mind. One was to shoot a lot of videos, not only for corporate donations that Heifer would want to try and elicit, but also video that we could use to generate awareness of the East Africa Dairy initiative in other parts of Africa as well. That’s why half of us went. The other half of us went to play the more traditional role of an advertising agency, which is to talk to as many people as we can, do some investigative research, take a look around at what the challenges are, see what’s really working to increase enrollment into East Africa Dairy, how all the pieces work together, and then bring those observations and information back so that we can start crafting some solutions for them.

JOEL: Heifer sent through a lot of materials to help us prepare. I pestered our contacts in Heifer quite a bit with a lot of questions about how the program worked, about how dairy farming in East Africa worked in general. I’m from Ohio so I know how farmers work, but it was clear that how farms work in Kenya is completely different from how farms work in the U.S. So we were trying to understand the day to day operations and how they work as part of the larger economy. Kenya does have a few of what we might call industrial farms, but the vast majority of the farm work done there is by small scale farmers, an acre or two of land, a few head of cattle.

DALE: We thought that the only way that you could do it would be to go and see what they did. You can imagine we had no lack of volunteers to go and make this film. We picked the natural people here, those with skills from a creative and film-making point of view, and off we went, 8,000 miles for milk.

KRISTEN: We were with a group of folks from Heifer who were the staff of the East Africa Dairy Development project, and we had worked out a schedule with them so that we were getting a sense of a range of farmers that we’re supporting. They’ve put these farmers into three different segments, A, B, and C farmers. A farmers are the ones that are just starting out, probably the most vulnerable. They maybe have one cow, they’re just being trained in ways to graze these cows in more modern farming techniques, so that they’ll be able to increase the milk production. We were able to see A farmers, B farmers, and C farmers. C farmers are those that are more reliant on their dairy production. They’re actually making a profit, they’re actually able to sell the milk and not just consume it at the home.

MITCH: We just wanted to interview some of these people on camera. They gave us an itinerary for Kenya that included multiple farms per day, and we pushed back and said, “Look, we don’t want to do multiple farms. We want to do, at most, one farm per day. And we’d actually like to go back to one farm maybe twice or three times, so that we can get to know the farmers a little bit better.” I’m not sure they understood why we wanted to do that, but they did their best to accommodate it.

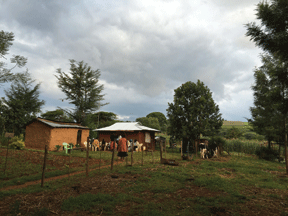

STEPHEN: The thing that we saw that surprised me is just how meticulous these farmers were. It didn’t matter if they were working with sticks collected from a nearby forest to make a fence or chicken coop, or working with a local distributor to put up water tanks to collect the water, to provide water for their family and for the livestock too. You get up close to these things, you get close to these farms, and it’s just amazing how meticulous they were in their craft and how inventive they are with what they have. Everyone loves to talk about how we recycle here, but they were recycling with their own ability to craft these things. That was one thing that I just didn’t expect. I expected them to be resourceful, but they were incredibly resourceful and meticulous.

JOEL: The biggest surprise for me was that the area in Kenya where we were did not look at all how I thought it would look. I thought it might look like Iowa, but Iowa is too flat. Dale thought that maybe it would look like Switzerland. It turned out to be incredibly green, incredibly lush, sizeable hills because there were mountains in the area. So the landscape of Kenya surprised me. When I thought of a small scale farm in Kenya, based on the pictures that we saw, I thought everything would be brown or dry, and it was the exact opposite. Everything was green.

DALE: What surprised me was how much they have embraced the program and how much it has changed their lives. I expected that it would’ve made things better, but when you talk to a woman who has gone from having a 30-cow dairy herd that produces somewhere between zero and four liters of milk a day to having a two-cow dairy herd that produces 14 liters of milk a day and whose kids now can afford school fees and whose family is now well-fed when before they were malnourished, that’s what surprised me, the profound impact that this program has had.

KRISTEN: When a family engages with Heifer, they are signing up for training and interactions with a whole host of field personnel that support them. They have to be all-in on that. Heifer takes a very academic approach to this training, and so what we brought to the table was very much similar what we do every day here at the agency, which is working out, in these farmers’ lives, where they are during the day, who they’re interacting with. If they’re bringing their milk to the milk hub, where the milk is processed, what are those touchpoints along the way where Heifer and East Africa Dairy could intersect with them to either bring awareness to the program, or to expand on the work that they’re already doing.

TRISTEN: One of the farmers that we met, her name is Rose and she is a phenomenal woman. She created a women’s group, a cluster of women in the community that get together every week. Rose gets them together and teaches them everything they need to know to take better care of their cows, to take better care of their families, to prosper. So sometimes it’ll be how to feed your cow and how to grow your own fodder for your cow so that your cow will produce more milk. But then sometimes it’s also a little bit of rules for living, the value of being accountable for your time, the value of being a good partner, the value of focusing on your family.

MITCH: We got hours and hours of footage, and we got some really good stories, really good personal testimonials from these farmers, which is what we wanted to do from the beginning, because the video that Heifer has right now has a very Western-sounding narrator. They have very little that is from the voice of the farmer. The first guy was terrified to be on camera, but his father was also there, and he said really great things. We went to – the very first thing we shot, actually, was one of the milk production centers, where people bring their milk. They call them hubs. So, we got a pretty good sense of the mechanics of what was going on from this guy, Isaac, who was running that hub. I was impressed with how much of an entrepreneur he was, his whole thinking is, “We started out with X capacity. Today we’re at Y, but the future holds a major upgrade. We’re going to need better equipment, we’re going to be able to offer better products,” and ultimately, it will all help the farmers, because it works like a co-op.

TRISTEN: Heifer doesn’t have unlimited funding to find ways to build communications and push them out to prospects. So we were able to see some really basic things that we could do to help them. For example, when we met Rose and these women’s groups and we videoed their stories, we found that these stories are incredibly powerful and their story of success as a group of women was incredibly powerful, enough so that it was worth spreading as its own story. These women are playing a major role in the survival and the prosperity of their families since they’ve started in these women’s groups. It’s a powerful story that could inspire other women if we make a separate video that’s just about the strength of the woman, right? The role that she plays on a dairy farm, the role that she plays in her community.

KRISTEN: One of the things that we identified earlier on is that a lot of these farmers got into the program by almost stumbling upon it. They might go past another person’s farm and see that they have a water tank or flowers in the yard or maybe they’ve been able to purchase a tractor. Once you see a family lift themselves out of poverty, you want to follow their example, and so that’s one of the things that we’re going to try to accomplish, trying to bring some of these success stories to life via either video, or with materials that we’ll build for the field personnel on the ground with Heifer.

STEPHEN: There’s a Swahili phrase we heard a lot that basically translates as, “Seeing is believing.” We heard from a couple of families that they’d be interested in Heifer’s East Africa Dairy as soon as they could see it working well for another family. But given the distances involved, that isn’t so easy. If they don’t have a farm that’s within walking distance of another farm that’s in the East Africa Dairy Program, it’s really hard for them to imagine. And Heifer didn’t have before and after pictures of what cows look like when you feed them better, or how much more milk they produced. It’s as basic as can be that if you want to show somebody how successful something is, you show them a picture. But Heifer doesn’t have that. So we are thinking in terms of a traditional awareness campaign, but we’re also trying to think how that awareness campaign could be distributed in ways where it provides more function. For example, one of the things that we saw was that Heifer was distributing what might be called a ledger to these farmers. It’s a blank ledger and pen so that they can start writing down the increased yields, what they’re feeding, what’s working, what’s not working. So we started to think, if a ledger book serves a really great function for these farmers, is that a place that we can start to include materials that show the success of other Heifer families? Also, there are ways to embed seeds in paper, and so maybe even the pages of these ledgers could contain sorghum seeds embedded in them. So it’s not just a ledger that they can use, but if they want, they can tear the pages out and plant them to grow the nutrients that they need. Those are the kinds of ideas that we’re trying to think of. Is there something that we can do that goes beyond the awareness campaign, that somehow provides a value added tool?

TRISTEN: Heifer has this role called a community facilitator. The community facilitator travels around the region of farmers – so they have a territory – and educates them on the cornerstones of Heifer, its philosophies for how to be prosperous. They teach those cornerstones, but they also teach animal husbandry, how to grow the fodder, how to take care of your cow, all of that. And they do regular visits. So these people in our minds are very similar to sales reps, right? They’re going out in the field and they’re trying to educate, or potentially even sell someone on the idea of the value of being part of this program. There is a commonality between the theory of having a community facilitator covering a territory and teaching to that of a sales rep covering a territory and selling and teaching physicians. So we saw a lot of similarities between what we do for our clients every day that can apply to some of Heifer’s field representatives, the community facilitators in Kenya.

KRISTEN: The actual tools that we are proposing to put in field are still, we’re still coming up with what those prototypes might be. Our goal is to try to get some pilots in the field in the next three to four months. We want to build some of these tactics or these programs for Heifer’s community facilitators and actually pilot them in some of the areas to see how they are received. Then the goal would be for us to – once we get a feel for how they do in Kenya – to actually roll these out in Tanzania and then making another trip to Tanzania to see them in field and then adapt them, to see if there’s any regionalization that would need to take place from a Tanzania perspective.

MITCH: We’re putting together a sizeable campaign. We’re in the beginning stage of the planning an in-country recruiting campaign, an awareness campaign for Heifer. We will not just limit ourselves to video, because, frankly, nobody has televisions there. But the video will play on – whatever we do for recruiting, we’ll play on these mobile training units, they have these giant semi-trucks, and when the side panels open up – they roll up like garage doors, and reveal a giant jumbotron on both sides. And then inside, in-between those screens, they have seating, so they’ll announce the training day, and drive this jumbotron truck out to those hubs. They’ll set out the chairs, and then they’ll play a series of videos for these people, and that’s how they get their training. But we’ll put together a little two to four-minute personal testimonial video of all these farmers and their success stories, because folks don’t really believe the benefits of something like Heifer until they actually see the benefits.

JOEL: I left with a sense of optimism for how much good could happen so quickly. More than 100,000 small farmers are in this program that’s been going on for a few years. They had impressive farms. Things looked professional or as professional as you could expect from single person farm in Kenya, and we had learned that they’d come into the program just eight months ago, six months ago, a year ago, and to see the change in their lives that happened in such a short timeframe, surprised me in a profound and positive way. It showed that even though a lot of what Heifer is doing is on an infrastructure level, that the actual individual lives of these individual farmers can improve drastically very quickly. It was really uplifting, it made you want to do more because you saw that it doesn’t take that much to flip that switch and have their lives transformed.

STEPHEN: The most moving evening that we had was when we spoke with a women’s group. Just 10 women sitting in this really small living room at one of the farms, talking about the changes that this East Africa Dairy program had created and how it impacted them, not just in terms of providing the extra income that they need, but the way it changed the way they related to their husbands and children and their expectations from life. It just changed them, and when you sit in this farm and listen to these women tell these stories, you can see on their faces just how much, how valuable, and how incredible it’s been for them as people. I don’t think anyone came out of that evening, after listening to those stories, feeling the same. It was just an incredible, moving experience. It really resets how you see yourself and what we take for granted over here. Makes you value not just the things that we have over here, but how you see people too. You come back changed for sure.

DALE: We’re certainly going to continue to support the effort. The next big thing is to figure out, number one, how we can help them more and, number two, to actually create this film which they can use. It’s been pretty hectic around here since we got back and so we’ve been devoting the time to it that we can but we’re still a long way off from making specific proposals to them, and we’re going to need to work with them to figure out what it is that they think that would be most helpful to them.

STEPHEN: I’m not sure businesses can survive now without a sense of social responsibility. The companies that prosper and are leading the way are the ones that take it on. Some of the initiatives that Patagonia has done, some of the initiatives that other brands have done showing how they support the environment or health initiatives outside of the products that they’re selling, they’re doing it because one, it supports a great cause, but two, that expectation is being set by each passing generation of consumers.

KRISTEN: We are just blessed as a group to have such a successful agency, and we always say that social responsibility is kind of within our DNA. We are a health and wellness agency and so we are invested in the health and wellness of not only our community here in Chicago but how we can impact the rest of the world.

TRISTEN: This was a really big step and an investment on the agency’s part to send us out there, but this was not a one-time trip. This is a trip that will establish the foundation for a long-term initiative, a long-term relationship. AbelsonTaylor has always been known for being generous and philanthropic, even in the way that it treats its employees. We are well-cared for. This is not a selfish agency. It’s really a very lovely place. Seeing the agency commit to something larger than just sending money every holiday season for this program was really nice, and I found it to be really inspiring.

DALE: I’ll tell you an interesting comment that a couple of people made, a couple of different farmers made, sort of independently. They said, “We know that westerners come to Kenya to see our animals. No one has ever come here to see us before.” I thought that was interesting. Because we came there not to see the elephants and the giraffes, but to see them.

MITCH: We do have this cultural barrier. I mean, we’re a bunch of mid-western, white Americans who – we have this sort of notion that we can somehow make life better for smallholder farmers in East Africa, and we’re very self-aware of the fact that we don’t think like they do, we don’t suffer the same problems. So we’re pretty sensitive to the cultural differences that we have, and as a result of that we’re focusing on core human truths. I don’t care where you’re from, what language you speak, if you’re hungry, you’re hungry; if your kids are sick, that’s bad. There’s nobody in the world who would be happy with the fact that their kids are sick and dying from malnutrition. So we’re going to keep our communication at that basic human level, which speaks to everybody, and honestly, I think, that’s a good exercise for us in our regular work.

DALE: We went over there thinking that there might be a new twist on how we can tell Heifer’s story, not this other goal of figuring out some new initiative but just how we could tell their story. When we got there, we realized as we interviewed the farmers and their wives that the best way to do it was to film the interviews of the farmers and their wives talking about the impact that Heifer has had, that we didn’t need a plot twist or a trick, that what we really needed to do was a straightforward telling of the way the EADD has affected the lives of these farmers. All we need to do is let these farmers tell their own story.