Beyond COVID-19 and RSV, emerging vaccines target less common conditions

Beyond COVID-19 and RSV, emerging vaccines target less common conditions

Published: Nov 16, 2022

By Gail Dutton

BioSpace

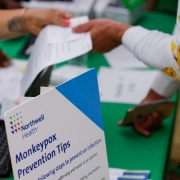

RSV, influenza, COVID-19 and monkeypox have dominated the headlines this year, but vaccines are also being developed for a host of other infectious diseases that may not come immediately to mind.

Lyme Disease

For example, Valneva, a French vaccine developer, is the only company developing a vaccine against Lyme disease. The work is being done in collaboration with Pfizer. VLA15, a multivalent recombinant protein vaccine, is currently in Phase III trials, with plans to enroll some 6,000 participants at up to 50 sites in Europe and the United States. It holds FDA Fast Track designation.

VLA15 uses an established mechanism of action for a Lyme vaccine that targets the outer surface protein A (OspA) of Borrelia burgdorferi, the bacteria that causes Lyme disease.

“OspA is one of the most dominant surface proteins expressed by the bacteria when present in a tick,” said Jerica Pitts, senior director, global media relations at Pfizer. “Blocking OspA inhibits the bacterium’s ability to leave the tick. Vaccination with VLA15, therefore, may prevent infection in humans and, consequently, prevent the development of Lyme disease.”

The vaccine covers the six most common OspA serotypes in North America and Europe, Pitts added.

Lyme disease is spread through the bites of ticks that are infected with Borrelia bacteria. It affects approximately 476,000 people in the U.S. and about 130,000 people across Europe. VLA15 works by targeting the six most common strains of Borrelia. The Phase II trial, involving 1,030 adults and children, showed strong immunogenicity and tolerability.

Participants in the ongoing Phase III trial receive the primary vaccine in the first year of the study and one booster about a year later. “Based on the findings, we will determine if a booster is needed,” Pitts said.

Epstein-Barr and CMV

Vaccines for Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) and cytomegalovirus (CMV), are two more examples. They have been pursued for decades but, “unfortunately, many of these efforts have had limited success – if any – in initial human trials,” said Sumana Chandramouli, Ph.D., senior director and research program leader, infectious diseases at Moderna in an interview with BioSpace.

Currently, there is no approved EBV vaccine. Complex virus biology and the virus’s use of multiple entry pathways have helped those viruses evade the immune system. A vaccine toolbox that – at the time – was limited contributed to those failures.

“We are now building on the learnings from these earlier trials, combining (those insights) with our latest knowledge of how these viruses infect humans and utilizing some of the newest tools, such as the mRNA platform, to make vaccines,” Chandramouli said.

Moderna’s mRNA vaccine platform confers one important advantage. “It allows us to combine several mRNAs into a single vaccine with relative ease, allowing us to tackle complex viruses such as CMV and EBV on multiple fronts,” she said. “Encoding for vaccines via mRNA also allows us to present these antigens on the cell membrane in a more naturally-relevant context to the body’s immune system.”

As part of its extensive vaccine pipeline, Moderna is developing two mRNA vaccines against EBV, a herpesvirus. Because more than 90% of the U.S. population acquires the virus by age 19, “The first one (mRNA-1189) is a prophylactic vaccine meant to prevent infectious mononucleosis in adolescents,” Chandramouli said. It’s in Phase I studies.

“Mono typically occurs when a teenager or a young adult contracts EBV for the first time. It can be debilitating and disruptive for several weeks to months, and can sometimes lead to serious complications with the spleen,” she added.

The investigational vaccine is made from four mRNAs that encode EBV envelope glycoproteins that help the virus enter the B cells and epithelial surface cells.

“The second EBV vaccine (mRNA-1195) is intended to address long-term complications of EBV infection in those who already have acquired the infection. The optimal age for administration of these vaccines will be studied during the vaccine development process,” Chandramouli said. This vaccine is in preclinical development.

Unlike its COVID-19 vaccines which, although highly effective, lose efficacy over time, Moderna expects the EBV and CMV vaccines to be more durable.

As Chandramouli explained, “Some viruses, like SARS-CoV2, evolve rapidly into new strains, thereby evading immune responses from prior vaccination. This contributes partially to waning immunity, requiring vaccines to be updated to match current circulating strains.”

Viruses like CMV and EBV, on the other hand, are less prone to such rapid strain evolution, as their sequences tend to be more stable. “Thus, waning immunity due to strain variation or evolution is expected to be less of a problem,” Chandramouli said.

An Intranasal Vaccine for AOM

Blue Water Vaccines is developing an intranasal vaccine for pneumo-induced acute otitis media (AOM), Joseph Hernandez, chairman and CEO, told BioSpace. “The condition is caused predominantly by a strep pneumonia that infects the ear and, in the long-term, causes antibiotic resistance…so this is an important issue with the pediatric population.”

Preclinical studies conducted by researchers at St. Jude Children’s Research Hospital, Emory University and Wake Forest University, have shown the vaccine, BWV-201, retains all the major antigenic virulence proteins of the virus and elicits an immune response without causing the disease. Basically, BWV-201 modifies the virus by deleting the signal recognition pathway. It is currently undergoing IND-enabling studies.

Blue Water Vaccines chose intranasal administration because, as Hernandez said, “Your nasal cavity is the (location of your) first encounter with these bacteria. Because of that, mucosal immunity is very important.” Studies in animals show a consistent, predictable mucosal immune response that reduces the ability of the bacteria to colonize the middle ear and, therefore, reduces the risk of middle ear infections.

“We want to do a clinical trial that looks at middle ear infection for the pediatric population,” Hernandez said, adding that his goal is to initiate human trials sometime in 2023. Because the nasal cavity is a natural infectivity pathway, “It’s an attractive form to look at for future vaccines.”

Source: BioSpace