Special Feature: Medical Cannabis Continues To Grow

The medical cannabis market in the United States, even with all of its restrictions, continues to be a fertile area not only for dispensaries, but pharma companies developing cannabis-derived drugs; and proponents say further growth can be generated by educating physicians about medical cannabis.

The medical cannabis market is well rooted and growing like mad, at least in North America. According to David Jagiesky in a July column for The Motley Fool, while the entire European cannabis market in 2019 totaled $260 million, sales in Canada during the first year recreational pot was made legal amounted to $677 million. In the United States, where medical cannabis is legal in 33 states, 2019 sales in Colorado alone were $779 million and analysts believe that retail cannabis sales, both medical and recreational, might reach $15 billion in 2020 and grow to $37 billion by 2024.

According to Marijuana Business Daily’s Marijuana Business Factbook for 2020, the industry generated an estimated $11 billion-$13 billion in 2019, propelled by robust growth in mature recreational markets such as Colorado and Washington state and rapid expansion in medical markets such as Florida and Oklahoma.

Although local dispensary sales have boomed as medical use of cannabis increased for COVID-related anxiety, as well as recreational use, the Factbook’s authors note that use might go down after the $600 a week additional unemployment benefits ran out at the end of July. “While cannabis businesses have fared exceptionally well so far, it’s still very much an open question as to how they’ll fare if no – or limited – additional financial stimulus is provided to the tens of millions of unemployed Americans,” these experts say.

Meanwhile, efforts to legalize recreational use have been stalled by pandemic-related difficulties with legislative meetings in Connecticut, Missouri, New Mexico, New York, Ohio, and other places.

Medical cannabis versus cannabis-derived drugs

One of the largest barriers to medical cannabis use is cost. Cannabis and cannabis-derived products with high levels of THC sold in dispensaries, such as edibles, are still illegal under federal law. Cannabidiol oil, which is extracted from the flowers and buds of marijuana or hemp plants, is non-intoxicating and if derived from a plant classified as hemp (containing less than 0.3 percent THC) can be sold legally in soaps and cosmetics or foods or supplements, so long as no medical claims are made. CBD products derived from marijuana, however, must be handled within state-licensed medical dispensaries. But neither medical marijuana nor CBD products are reimbursed by insurance, with the exception of workman’s comp in certain states – New Jersey, New Mexico, and Minnesota – where judges ruled that an insurer should pay for medical marijuana to treat certain conditions. As for CBD, products on the market wildly value in purity and quality.

One of the impediments to cannabis research, which has made it less attractive to pharma, is the difficulty of getting access to marijuana. For those researchers who get a DEA license for federally funded research, they have access to only a single source from the University of Mississippi. Bloggers have made fun of this low-THC, low CBD strain for years. In fact, researchers at the University of Northern Colorado, in analyzing the genetic variance of the strain, found it was closer to hemp than the marijuana available in dispensaries.

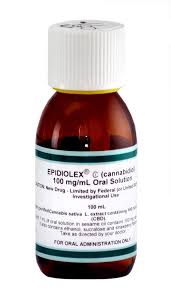

GW Pharmaceuticals’ Epidiolex during June 2017 became the first-ever plant-derived cannabinoid prescription product to gain FDA regulatory approval.

Still, a few companies have decided to go the FDA route and develop and get approval for their own THC or CBD-derived products. Epidiolex, from GW Pharmaceuticals, in 2018 became the first drug approved by FDA that is actually derived from marijuana. The drug – a purified form of cannabidiol – is available for the treatment of seizures associated with two rare and severe forms of epilepsy, Lennox-Gastaut syndrome and Dravet syndrome, in patients two years of age and older.

At the time of the approval, former FDA Commissioner Scott Gottlieb stated that, “We’ll continue to support rigorous scientific research on the potential medical uses of marijuana-derived products and work with product developers who are interested in bringing patients safe and effective, high-quality products. But, at the same time, we are prepared to take action when we see the illegal marketing of CBD-containing products with serious, unproven medical claims. Marketing unapproved products, with uncertain dosages and formulations can keep patients from accessing appropriate, recognized therapies to treat serious and even fatal diseases.”

U.S. approvals for “THC” products have been for synthesized molecules. The first on the market was dronabinol, marketed as Marinol by Unimed Pharmaceuticals, a division of Solvay. Marinol initially was approved as a Schedule I product in 1985 for the treatment of nausea and vomiting in cancer patients, and in 1992 for appetite stimulation for AIDS patients. The product became a Schedule III drug in 1999. Marinol is a synthetic version of Delta-9 THC naturally found in the plant.

Nabilone, marketed as Cesamet by Valeant Pharmaceuticals, is a synthetic cannabinoid similar to THC. The product was initially approved by FDA in 1985, but then was removed from the market until 2006, when it was reapproved. Nabilone also treats nausea and vomiting in patients undergoing cancer treatment.

One company seeking to develop a CBD-like prescription product is Doylestown, Pa.-based Kannalife Inc. The company has been working on its laboratory-created CBD-like molecule, KLS-13019, as a non-opioid alternative to prevent and reverse neuropathic pain and for the treatment of other types of pain.

According to Dr. William Kinney, Kannalife’s chief scientific officer, “One of the problems when we started research was that cannabidiol was a controlled substance, a Schedule I drug, and so we had to get a DEA license. But that was not a problem to get and we had to buy everything through that DEA license.”

The company had to acquire CBD “really to evaluate it,” Dr. Kinney says. “We wanted to understand the benefits and drawbacks of CBD.” The company benchmarked the substance, finding that it was a “pretty good” neuroprotectant but had some drawbacks, particularly that it was not orally absorbed well. And while CBD protects neurons at a concentration of 2 µM, it was actually injurious to the hippocampal neurons at 30 µM.

Kannalife began making the company’s own CBD-derived molecules, with the goal of improving the water solubility and bioavailability. “After we made about 20 molecules, we identified KLS13019,” Dr. Kinney says. “It was quite a bit more potent, having an effect at 30 nanomolar, versus 2 µM for CBD. We also found it was less toxic to hippocampal neurons, that was unexpected, we didn’t see toxicity until about 300 µM. So being efficacious at 30 nanomolar and seeing toxicity at about 300 µM, that’s quite a large safety window.”

With the test of bioavailability in mice, Kannalife found KLS13019 was better than CBD. “With CBD, only 6 percent of an oral dose gets into your bloodstream, whereas our molecule, it was about 60 percent of the dose was absorbed through the gut.” And with more potency, better safety and better bioavailability, the drug offered another advantage over CBD: it was an original molecule that the company could patent. “Now we have patents throughout the world,” Dr. Kinney says.

As with many research-based companies, one of the biggest challenges remains how to fund the program. But CEO Dean Petkanas says Kannalife has been developing an OTC called Atopidine, another “CBD inspired” molecule created by the company. The product was shown in preclinical testing to decrease inflammatory cytokine (TNFα, Il-1β, CXCL5 and IL-8) levels at concentrations 50 times less than toxic levels. Atopidine was effective in an in vitro photoaging experiment with anti-inflammatory action based on IL-6 inhibition against UVA irradiation in cultured human dermal fibroblasts cells. IL-6 is an immune system signaling molecule that has been shown to promote inflammation.

In April, Kannalife announced that the studies performed on Atopidine suggested that it has outperformed cannabidiol in preventing inflammatory responses relevant to UVB-radiation. Although both compounds were effective in preventing the release of TNF-alpha (TNFα), only Atopidine was found to be effective in preventing the release of IL-1-beta (IL-1β) from human epidermal cells. This suggests that Atopidine may be more effective than CBD in preventing inflammatory responses relevant to UVB-radiation.

The company is hoping to have Atopidine as a finished product by the end of 2020 for commercial use as an emollient to address a number of skin care and personal care needs.

While medical marijuana dispenaries have a booming business, the future of medical marijuana is in approved pharmaceutical products, Dr. Kinney believes. While dispensary marijuana is sought by patients as a non-opioid alternative to treat chronic pain, the THC these products contain is impairing, And CBD has its own issues, particularly liver toxicity. In animal studies, the company found that KLS13019 could prevent chemotherapy-induced chronic pain before treatment as well as reverse it; CBD did not.

“So we think we have a more profound effect on treating chronic pain, and we’re looking to evaluate our product in other pain models,” including diabetic neuropathy and osteoarthritis, Dr. Kinney says. Other advantages KLS13019 has over CBD are the ability to get a consistent dose, “and we think we’re more efficacious.” Clinical trials should commence in 2021.

From healthcare advertising to medical marijuana

As dispensaries have boomed, some traditional pharma-centric medical advertising executives might be casting eyes at medical dispensaries and wondering if there is a way to work with them. One person who would be able to tell them is Kyle Barich, the former CEO of CDM who left the healthcare communications agency and in October 2019 became chief marketing officer of Holistic Industries, one of the largest private multi-state operators in cannabis.

According to Barich at the time, “I believe that the cannabis industry is ripe for brands that speak to the millions of people who could benefit from the plant’s increasingly evidenced-based properties that help people heal and enjoy their lives. I can’t think of a more exciting opportunity for someone with my background than to help shape the fast-emerging health and wellness category that is just beginning to embrace cannabis.”

Catching up with Barich recently, he’s still passionate about the cannabis industry and the role he has in it. Barich says he was drawn into the industry through one of his college friends from the University of Michigan, who has a cannabis law firm. “He was always trying to get my head into it, since we worked in such similar industries, and the cannabis industry itself doesn’t have a lot of grownups,” he jokes. “With my interest in bringing what I know about healthcare advertising, I got involved as an advisor and an investor in the industry. I started investing in companies that I thought were interesting and started advising those companies.”

One parallel he noted between traditional pharma and the cannabis industry is that when it comes to the patient talking with the physician, conversations can be awkward. Barich had worked on Pfizer’s Viagra for erectile dysfunction, and just as ED patients were reluctant to talk with their physicians about their problem, there were patients who felt like they could not discuss medical marijuana with their providers.

And with medical marijuana, “There is a lot of ‘it depends’ in this conversation,” Barich says. “It depends on which doctors, and it depends on which consumers, and it depends on which state we’re in.”

The biggest problem is that most physicians have not learned about cannabis medicine or endocannabinoids in medical school, he says. “That whole field of medicine is relatively new, and as a result, only 9 percent of physicians have been taught by medical schools about endocannabinoid medicine.”

Meanwhile, countless consumers are coming into their doctor’s office and asking not only about CBD, but THC and the information passed on to them by a relative or friend about the use of medical marijuana for sleep or pain.

“And doctors don’t like you coming into their office with questions that they don’t have the answers to,” Barich says.

Interestingly, most physicians, especially the ones Horizon plans to target, do not have personal taboos against medical cannabis, he adds. “But if you go to a physician who is over, say, 50, chances are they are less likely to accept it.”

There are also specialties that are very open and accepting of patients seeking medical cannabis advice – for example, anyone who uses holistic medicine, or oncologists, who want to do everything possible to keep their patients alive and with the best quality of life. But doctors in more acute settings such as anesthesiologists or orthopedic surgeons are going to be less accepting. “It’s a cultural shift of who they are,” Barich says. “But the stigma with doctors is less than we thought.”

As far as traditional healthcare advertising agencies getting into the cannabis industry, there are a lot of barriers, Barich says. For example, for an agency such as CDM, a publicly traded U.S. company, “because cannabis is federally illegal, we were not permitted to work with cannabis companies.” That prohibition remains the No. 1 barrier.

“And for a lot of healthcare advertising agencies that I’ve seen, the fear of existing clients, what they are going to think,” Barich says. “When that press release goes out, saying the agency took on a cannabis firm, what is the reaction of your pharma client going to be like, or other conservative clients?”

Besides creative agencies, there are media and PR agencies, and all of them face barriers, Barich says. “You think pharma is regulatorily challenging, cannabis has its own restricted media channels.” Cannabis is federally illegal, but even though 33 states allow it, each has its own regulations. Because of these restrictions, Google and Facebook do not accept paid cannabis advertising.

“So the focus is going to be programmatic, geotargeted to that location; print; out-of-home – billboards are really popular – and then sort of on the fence are broadcast and radio,” Barich says. “Howard Stern took MedMen advertising, but Sirius is saying they’re not so sure. They change. One month they say, ‘No problem,’ the next month they say, ‘No.’”

MedMen launched the first-ever of its kind radio advertisement for a cannabis company in May 2018 on Sirius XM. The 30-second and 60-second spots focused on medical and adult use. In February 2019, MedMen premiered its first TV ad, which was directed by Spike Jonze. The ad “The New Normal” is a brief look into the history of cannabis legalization narrated by “Grey’s Anatomy” actor Jesse Williams.

For independent healthcare agencies who are not part of networks and can work within a state, there really is no barrier to entry, Barich says, but adds that just as consumer agencies found healthcare advertising complex, there are complexities to the medical cannabis market. An independent healthcare advertising agency might be better able to adapt to these complexities than a consumer shop. “It would seem that there would be fewer barriers,” he says.

There are other differences between the pharma and medical cannabis industries. For one thing, pharma companies deal with the FDA, but medical cannabis companies are regulated by a state’s Department of Health. And unlike pharma companies, medical cannabis companies handle their products from seed to sale – growing the plants, processing them, extracting the compounds, creating the products, and then selling those products in their own stores. Holistic is a multi-state operator, and like other MSOs, copies its business structure in one state and just uses that in the next state. The company has 20 stores in D.C., Maryland, Pennsylvania, Massachusetts, Missouri, and California.

As chief marketing officer, Barich is “growing a greenhouse of brands” for Holistic Industries, and has special plans for the medical brand, which he anticipates unveiling in the next few months. There is already an ad agency, a PR agency and a medical education firm on board, he told Med Ad News.

Rob Dhoble, a past Med Ad News’ Advertising Person of the Year, also has been advocating for the medical cannabis industry, but through a healthcare agency network. However, he is not involved in advertising, but education, through Havas ECS, which was launched in 2019 by Havas Health & You.

The agency is the only strategic advisory and education company focusing on the endocannabinoid system, trying to address massive gaps in the scientific understanding across the medical, public health, wellness, regulatory, patient advocacy and brand communities. Only 13 percent of medical schools offer any instructional material on the human endocannabinoid system (ECS), a biological system only discovered in the mid-1990s that regulates many aspects of human health and well-being.

Havas ECS was formed because there was a commitment by CEO Donna Murphy of Havas Health & You and the executive team “to lead in this space, whatever this space would be,” Dhoble says.

Physicians are struggling with patient demands for medical marijuana cards not only because they lack the scientific knowledge about dosing and potential interactions with standard medications, they also are not covered under malpractice policies, Dhoble points out.

If cannabis is changed to a Schedule II substance, “You’re going to see a lot of doctors rush in,” he says.

Meanwhile, patients are struggling with questions about how to handle their other medications if they are also using medical marijuana, Dhoble says. “What can you do? Well you have to go to a doctor who is certified in endocannabinoid medicine. And we grow that list every day.”

Havas ECS’ physician education course is sold through a number of different portals, including the Medical Society of New Jersey, which has endorsed the course. “That’s been my job, to lay this educational foundation, perhaps in a group practice, perhaps in a state medical society, perhaps as part of an insurance product that mitigates malpractice insurance with better training,” Dhoble told Med Ad News.

But compared to other countries in their use of, and knowledge of, medical cannabis, “We [the United States] are so stuck in the mud,” he laments. “What is a booming business in Canada – where all the hemp we planted here in this country had to come from, by law, until very recently – the Canadians have been leaps and bounds ahead of us. They’ve established rules for CBD, without saying they’ll get to it one day like our FDA does.”

For advertisers who want medical marijuana clients, this means “you can infer lots of things, but you can’t say lots of things … you have to leave a lot of it to the doctor/patient relationship. And if you have education powering up that relationship, you can have a really high expectation for care.”

According to Dhoble, for example, “Most people don’t realize that medical cannabis can treat your condition without getting you high. Different combinations of cannabinoids – THC and CBD being two of a hundred – have different effects. There are CBD oils available in dispensaries with different ratios of CBD to THC, for sublingual administration, and while the THC opens up the receptors enough to let the CBD work, and the CBD is so overpowering to the THC that it nullifies the effect of the euphoria.”

A doctor who takes Havas ECS’ course would know that, and will bring it up with patients if relevant, he says. “And most doctors are being asked every day, ‘What about CBD, what about medical cannabis?’ And that’s where we’re focusing most of our efforts, with the neurologists, the oncologists, the pain medicine specialists.”

Hospital-based anesthesiologists also need to know about how the use of medical marijuana can affect patients and their tolerance for anesthesia. “If the doctor plays the game of ‘Don’t ask and don’t tell,’ they run the risk of requiring more anesthetic to get them under if they are a regular cannabis or CBD user, or maybe worse yet, they go under but they come out of it midway through a surgery,” Dhoble says.

Havas ECS’ course is a world standard one, he says, in which any doctor, nurse practitioner or PA can become certified, and the agency is working on courses for other specialties as well.